Part 1/3

Over the past decade, “private credit” has become one of the most widely used — and most misunderstood — labels in the investment world. Open any financial newspaper and you’ll see the term applied to unitranche loans, consumer credit platforms, trade-finance funds, card-receivable ABS, and even settlement-flow programmes run by payment institutions.

A recent example illustrates the problem. When First Brands, a US auto-parts manufacturer, collapsed under the weight of complex factoring and payables programmes, much of the coverage framed the event as “another sign of stress in private credit”. Yet very little of what sat inside that structure looked anything like the sponsor-backed, multi-year loans that investors typically imagine when they hear that phrase. (Besides the fraud allegations) It was a tangle of receivables sales, claims, disputes, and operational failures — not traditional corporate lending.

That kind of shorthand has consequences. If a five-year sponsor loan and a three-day factored invoice are casually grouped under the same heading, the differences in risk, behaviour and recovery pathways become almost invisible. And when visibility disappears, investors end up with a blurry map of a world and questionable risk pricing.

So before we can talk about opportunity, scalability or portfolio construction, we need to sharpen the language. And that starts with the word credit, which quietly carries two very different meanings.

Why “credit” means two things at once

In everyday allocator conversations, credit is often used in a broad economic sense: if someone owes money and might not pay, the exposure is “credit”. Simple.

That wide definition sweeps in everything from corporate loans to trade receivables, from credit-card pools to settlement claims in a payment network. They all involve a payment obligation; they all carry non-payment risk.

But there is also a narrow definition, the one used by lawyers and structurers. In this more technical sense, credit means something very specific:

- there is a borrower,

- there is a lender,

- the asset is formally documented as a loan or credit facility,

- and it sits on the borrower’s balance sheet as a liability.

When specialists say “stress is building in private credit,” they almost always mean this narrow world: direct lending, sponsor finance, ABL revolvers, NAV loans. These are long-dated, borrower-centred exposures tied to corporate leverage and refinancing cycles.

Receivables programmes and settlement-flow finance live in the broader universe of credit risk — but they are not loans. Investors in those structures own claims, not loan assets. And confusing the two makes it harder to understand how different forms of credit behave under stress.

A quick accounting detour - Balance sheet impact: Liability vs. Liquidity

The structural difference also has a profound accounting impact that defines the economic outcome for the selling company:

- Loan-based credit (direct lending, ABL): The funds received are recorded as a liability (debt) on the borrower’s balance sheet. This increases the company's leverage and impacts key debt metrics.

- Claim-based finance (true sale factoring): The transaction is typically structured as a sale of assets. This removes the accounts receivable asset from the balance sheet and avoids recording a corresponding liability. This distinction is often a primary motivator for companies, as it uses the asset pool to generate liquidity without increasing formal debt leverage.

Why allocators blend everything together anyway

There is another structural reason the terminology blurs. In institutional portfolios, private credit is not a regulatory classification — it is an allocation bucket.

From the perspective of a CIO or investment committee, anything that is illiquid, yield-bearing, privately originated, non-bank, and exposed to non-payment risk tends to fall under the private-credit umbrella. In that broad portfolio map, five-year corporate loans and five-day receivables both live in the same high-level box, even if they live very far apart at the level of structure and behaviour.

This is why even sophisticated LPs can describe trade receivables, card pools and settlement flows using the same vocabulary they use for sponsor loans. The label “private credit” is doing too much work — and not very good work at that.

To navigate the space properly, investors need a better starting question.

A simpler way to cut the market: lending vs buying a claim

Instead of asking “is this private credit?”, a more useful diagnostic is: Am I lending money to a borrower, or am I buying a financial claim on cash flows that already exist?

This single question helps clarify what sits on each side of the credit universe.

Loan-based credit: Funding borrowers

You give capital to a company or SPV.

They owe you principal and interest.

Your exposure lives on their balance sheet.

Claim-Based Finance: Funding Claims and Flows

You buy receivables, invoices or settlement claims that arise from economic or payment activity. You are not funding a borrower; you are funding the flow of commerce.

Both involve non-payment risk. Both generate yield. Both are “credit” in the broad sense. But they behave nothing alike, and treating them as variations of the same animal obscures the differences that matter for portfolio construction.

What defines loan-based credit

Loan-based credit is familiar territory: direct lending, unitranche loans, mezzanine tranches, ABL lines. In all these cases, the investor underwrites a borrower’s business model, leverage, cash-flow profile, governance and refinancing path. The exposure tends to last for years; plenty of things can go wrong over that horizon.

When loans run into trouble, stress typically unfolds slowly. Metrics erode, covenants are reset, sponsors negotiate amendments, and only later — sometimes years later — does the problem crystallise in restructurings or insolvency. Loan-based credit is, at its core, an exercise in projecting future corporate solvency.

What defines claim-based finance

Claim-based finance begins somewhere entirely different. Here, the asset is not a loan but a receivable or settlement claim tied to a specific transaction:

- a shipment that has already been delivered,

- a card transaction that has already occurred,

- a settlement receivable in a payment rail.

Instead of underwriting a company’s long-term future, the investor underwrites near-term performance of economic activity that has already taken place. Many risks that matter for corporate loans — strategy drift, leverage creep, refinancing risk — simply do not have time to materialise.

Perhaps most importantly, the exposure is often highly granular. A portfolio might hold thousands or millions of small receivables, each tiny in size, each amortising quickly. Risk becomes statistical and data-driven rather than idiosyncratic.

When stress appears, it usually appears fast: a spike in disputes, a breakdown in settlement processes, an operational failure in the payment chain. Because the assets turn over so quickly, problems are visible almost immediately in the data.

Claim-based finance is ultimately about underwriting flows, not balance sheets.

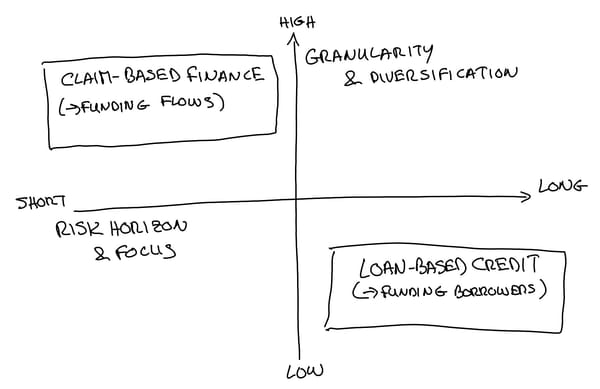

What really changes when you move from loans to claims

Three differences shape everything else.

1. Time horizon

Loan-based strategies carry multi-year exposure to corporate solvency.

Claim-based strategies typically revolve within days or weeks. The risk window is short and tightly linked to completed activity.

2. What the risk is tied to

Loans are anchored to the entire borrower’s business.

Claims are anchored to specific transactions, obligors and the operational rails that move cash.

3. Granularity and diversification

Loan portfolios are typically built from a few dozen chunky exposures.

Claim portfolios are built from thousands or millions of small ones, generating smoother risk behaviour and fewer tail events.

These structural differences make claim-based finance behave very differently from loan-based credit in drawdowns, in normalised markets and in recovery scenarios.

Why the distinction matters now

It might be tempting to dismiss this distinction as theoretical. Both kinds of strategies sit under the private-credit allocation; both generate yield; both involve non-payment risk.

But investors who treat them as interchangeable risk missing the point.

A fund filled with five-year sponsor loans will behave nothing like a vehicle owning three-day receivables. Their liquidity profiles, drawdown patterns, valuation dynamics and correlation to macro cycles are fundamentally different.

Investors exposed to loan-based corporate credit experienced one kind of stress path; those exposed to receivable pools experienced another.

Understanding the difference between funding borrowers and funding flows is not splitting hairs. It is the baseline for mapping risk correctly — and for understanding how the modern private-credit universe is evolving far beyond its loan-centric roots.

Where we go next

This article set out the conceptual distinction between loan-based credit and claim-based finance. In Part 2, we step into the allocator’s shoes and examine how different investors should think about these two universes: who each world is suited for, how they map into portfolio buckets, and where claim-based finance fits within the emerging landscape of specialty finance.

In Part 3, we look at scale: why the claim-based universe — particularly around payments and commerce — may represent a far larger opportunity set than loan-based private credit, and what that means for portfolio design over the next decade.

For now, the most important question for any strategy marketed as “credit” is surprisingly simple: Am I funding a borrower, or am I funding flows?

The answer changes everything.